The Lean-to at Luton Hoo Walled Garden

I expect many visitors experience déjà vu when they visit Luton Hoo. Gosford Park, The Secret Garden, Sexy Beast, Mr Turner, Wilde, Rebecca, and one of my favourite films, Empire of the Sun, were all filmed in either the old stately home, the walled garden or the Victorian outhouses, along with at least 50 other films and dramas. I experienced the feeling as I drove up the mile-long Lime Tree Avenue, which was rationalised when I learnt more about the usage of this estate.

As you drive up you just get a glimpse of Luton Hoo House, but it was the walled garden that I had been invited to, rather than the posh hotel, on a hot June afternoon. Six months later, and I was thinking about this trip after a glimpse of some Victorian out-buildings on TV; that looks familiar, I thought, and then of course I was reminded of my visit. There is so much to say about these gardens, not least that once they were deemed to be second only to Kew in the botanical garden ratings.

Designed by Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown, the gardens are quite typical of the era, except for the walled garden which is fairly unique. The design is an octagon, which was thought to have been at the behest of the owner at the time, the third Earl of Bute (1719-1792). A very unpopular Prime Minister for a year in 1762, Bute was also a botanist, and created these gardens for his large collection of plants. In the late 18th century, inconveniently for the kitchen staff, landscapers and garden designers started placing walled gardens well away from the English country house because they were considered to be a blot on the scenic view; useful but not to be seen, a bit like the servants. Capability Brown’s intention was to blend the gardens into the surrounding natural elements, a gardenless landscape, and certainly without the ugly food-growing business visible. As such, this walled garden is set at quite a distance from the Luton Hoo house.

The Walled Garden at Luton Hoo

Bute’s desire for an octagonal shape is not entirely known, but he was an amateur astronomist which may explain why the garden has been designed to exactly capture the solstices and the equinoxes. As Patrick Powers explains:

“… the red line from the centre of the garden to the North East wall indicates the most northerly direction of sunrise on June 21st mid-summer’s day. Similarly the red line from the centre to the North West wall indicates the most northerly direction of sunset at mid-summer. The lines to the South East and South West walls of the garden show the directions of sunrise and sunset respectively for mid-winter, December 21st. The lines to the East and West walls show the position of sunrise and sunset at the Equinoxes, 21st March and 21st September when the sun rises due East and sets due West with equal periods of day and night...” (ppowers.com)

Google earth image showing the Solar alignments in Luton Hoo walled garden (Patrick Powers)

There are theories that this was not just a fun experiment by Bute but had various practical advantages. One of these is that it was a useful indicator for the gardeners to know when to plant and harvest depending upon where on the octagon the sun was shining. We may think that surely they knew when to do all these jobs, but managing time had got a bit complex around then. Further to the Calendar (New Style) Act of 1750, on the 2nd September 1752 England, and its colonies, moved from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar. This meant that we lost 11 days of the year. The situation was further complicated by the change of the start of the calendar year from 24th March to 31st December. At least now we were aligned with Scotland and much of Europe. But in the same way that some of us still struggle with the clocks going back and forward, no doubt these changes in the second half of the 18th century took some getting used to, especially as the tax year remained the same. Luton Hoo walled garden was built just 11 years after all this. I wonder if the gardeners really did spend time examining where the sun shone on the wall before they planted their potatoes and peas. From what I have read about Lord Bute, I can just imagine him ordering them to do so in the most complicated manner. Perhaps they just nodded and said Yes m’Lord (you’re completely bonkers) and got on very successfully with what they had always done.

The point of a walled garden is to help protect fruit and vegetables from the elements (and from wildlife) and in doing so it creates something of a microclimate. Bute was known to be experimenting in planting peaches and nectarines, still quite novel then, so perhaps his octagon provided additional warm walls for these tender trees. Unusual fruit growing was the new horticultural trend in the 18th century and this five acre enclosed garden certainly had plenty of wall space for espaliers.

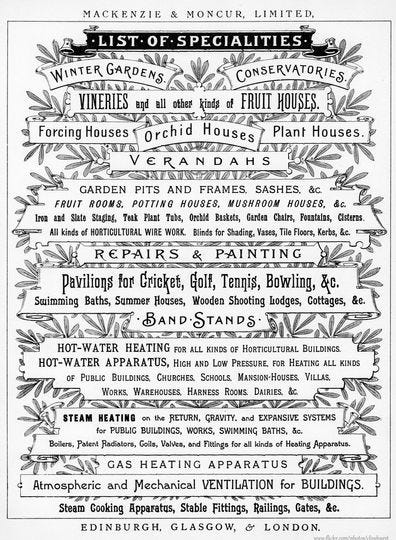

Bute, from whom plants in the genus Butea get their name, died from injuries sustained during a fall when collecting plants from Hampshire cliffs. A subsequent owner of the estate, Sir Julius Wernher, commissioned Mackenzie & Moncur to install a series of glasshouses in the walled garden. Well-known specialists of the time, they had built the fabulous glasshouses in Glasgow’s Botanic Gardens and the wonderful Palm House in Sefton Park, Liverpool, among many others, and they are still going strong. In 1903 they put in the central octagonal wooden-framed fernery, each side of which are three straight glasshouses and along one wall a huge lean-to.

Advertisement for Mackenzie & Moncur https://www.mackenzieandmoncur.co.uk

The central fernery

Rather mysteriously Sir Wernher sliced the octagon in two with a wall down the centre, which I think is rather a shame as you cannot quite appreciate the full extent of it, and he increased the height of the walls by three foot, perhaps for extra protection as it is quite an exposed site, being a hoo.

Sadly, but perhaps even more filmic, the garden fell into rather gothic but graceful decay, although it is now slowly and painstakingly being restored by a wonderful team of volunteers. They have removed the harmful plastic that was covering the timber and any remaining glass, and are working to preserve the lovely wooden frames, each piece of timber at a time. It is highly unlikely that they will be re-glazed but I suppose who needs more glass in this increasingly warmer world. The skeletal timber frames are eerily graceful and with cleaning and restoration, will provide a very atmospheric setting for a new film. I could do with help from these guys on my allotment glasshouses, or glasshouse I should say, now that my lean-to has collapsed.

Volunteer working on restoration of the glasshouses

Whilst Luton Hoo House was sold by Sir Wernher’s descendants, the family still own and manage the walled garden which has been transformed by this busy hub of people giving up their time. Researchers, historians, gardeners, carpenters, and anyone with reasonable DIY skills, are utilising these in a great collective purpose. Based on a combination of plans of the original garden, and memories from gardeners who were employed here before it lapsed into neglect, they are recreating a magical space which is helped by growing many of the same plants from long ago. This garden is definitely worth a visit if you can get here on a Wednesday, the one day of the week when it is open to the public.

Iris germanica (Bearded Iris) interspersed by Salvias

There is something about old glasshouses that I really love. I think it’s the combination of an elegant structure which is also home for wonderful plants and from the windows of which you often have a fantastic view of a world of greenery. Lean-to’s in old walled gardens are particularly beautiful with their peeling paint, great old iron heating pipes, the wind-up vents and decorative iron girders. It’s all so vital and vivid, I could live in one. Here, despite having no glass, a lonesome fig and an old grape vine thrive. The emotional final scene of Empire of the Sun was filmed in a conservatory somewhere on this site, which stood in for the Red Cross Refugee camp, when the protagonist, (J G Ballard as a child), is eventually reunited with his parents.

Grapes and a fig thriving in the glassless glasshouse

Aeoniums and Geraniums providing a blast of colour

Around the back of the walled garden are three sunken glasshouses which have been fully restored with all their glazing. Bute and his team of gardeners would have been astounded to see one of them full of cacti as it is today.

The sunken Cacti glasshouse

There were lots of interesting out-buildings here too; some full of old tools that were being restored, a glorious Potting Shed, a Vegetable Washing House, a Seed House, a Bulb House, a very dark Mushroom House, A Farrier’s workshops and the Head Gardener’s office; it went on and on. I suppose every big estate had all of these and more.

The farriers workshop

I was chatting to the volunteer in the farriers shed who told me that it was like working on an archaeological dig. They just keep finding things; pitchforks, spades; saws, chisels, all sorts, and he was having a great time, fixing these up each Wednesday. I had a similar experience, when I first got my allotment. The previous owner had died and his wife didn’t want any of the things left there, much of what she had thought he had taken to the tip long ago. And what a lot of things he left! Like many allotment owners he collected junk, in case it could be useful one day, and there was tonnes of it. Although I did have endless journeys to the tip, amongst it all I kept discovering treasures; a very long-handled sturdy spade, a turf-lifter, a hand plough which is useful for drawing out seed beds, a riddle, a pit full of wonderful old grey stones, and some nice terracotta pots. It went on and on.

The potting shed with a great selection of riddles

The Mushroom House

In 2013, three hundred years after the birth of Bute, and a totem to his love of philosophical instruments, an analemmatic sundial was installed in the walled garden, designed for humans to act as the gnomon. This was a first for me and what a great idea, if you have the space. Although I couldn’t quite get it to work. My shadow was meant to tell me the time but clearly I was standing in the wrong place, as is often the case.

The analemmatic sundial

Back up north on the allotment I looked at my tumbling glasshouses with some dismay. My restoration of these, which were hand-built from scrap by my allotment predecessor, has not been very successful. As is apparent, I can’t say that I have much in the way of woodwork or glazing skills. The lean-to ‘pavilion’ had become a lean-away and I didn’t feel entirely relaxed sitting under that roof. So, after some thought and with the help of my youngest son, we dismantled it before it collapsed. What to do with it next? Another project to think about.

My allotment glasshouses

And after..