Chideock Manor

Following my return to the UK, my first trip to proper British countryside was to West Dorset where I was staying in a lovely converted pigsty in a relatively remote hamlet, Ryall. Here the roads reduce to tiny, winding lanes, bordered by hawthorns and birches which, when they stretch out their branches to the trees on the other side, turn the lanes into increasingly tapered, emerald-green tunnels.

The drystone walls are bursting with mosses, lichens and ferns; Blechnam spicant, Dryopteris felix-mas (Male Fern), Polystichum aculeatum (Hard Shield Fern) and Asplenium scolopendrium (Hart’s-tongue Fern). The walls disappear beneath banks adorned with a plethora of flora; masses of primroses (Primula vulgaris - Vulgaris meaning ‘common’ rather than vulgar); Yellow Stars of Bethlehem, (Gagea lutea), purple Periwinkle (Vinca minor), the delicate white petals of Addersmeat (Stellaria holostea), the succulent greens of Pennywort, (Umbilicus rupestris), and interrupted by the occasional Lords and Ladies (Arum maculatum) whose common name refers to its genitalia like flower!

Arum maculatum (Lords and Ladies)

Gagea lutea (Yellow Star of Bethlehem)

Addersmeat or Greater Stitchwort (Stellaria holostea)

Pennywort (Umbilicus rupestris)

It was a blissfully sunny but cool Spring day; ideal weather for me. Not for the first time did it dawn on me how much I love the British countryside and I could not help but compare this to Asia, where the heat slows you right down and the humid forests are dauntingly still, silent and almost impenetrable. Indeed I wouldn’t dare go off the footpaths there. In comparison, here you can wander at will across moorland and field via old well-trodden footpaths, and stop and listen to the buzzing of insects, bird song, and the fluttering of leaves. It feels relaxed and easy. And from the moment I left my pigsty, I saw no one else at all on my morning stroll.

Common periwinkle Vinca minor

My plan had been to walk to Chideock Manor gardens. However, I had been so focused on the route there rather than the place itself, that it wasn’t till I left the house that I checked the website and realised I needed to make a prior appointment. I duly rang and spoke to a woman who I assumed was the Lady of the Manor. She was agreeable to me visiting today and explained there’s a £10.00 charge. And cash only! As I had no cash that meant walking back to the house, picking up the car and driving to a cash machine, which she helpfully provided me with detailed instructions for. ‘See you at 2.00!’ she said.

After a very long diversion, I decided to drive straight to the Manor, rather than park at Ryall and walk again, and at 2.15 pm I swept up the gracefully curved, gravel drive bordered by majestic pines, and parked in front of the mansion as if I was a grand visitor, albeit in my muddy, scratched Skoda fabia. The Manor loomed over me providing welcome shade from the blistering Spring. But it was deserted and so after hanging around, peering through gates and calling out ‘Hello!’ a few times, my voice echoing back at me from the old stone walls, I just stood for a bit, taking it all in.

The view from the front of the house was of lawns and lazy meadows which dropped down to a lake in which the trees were perfectly mirrored. Beyond the water were woods, a patchwork of Dorset fields rising up to gentle hills. Such a view from a large house is of course partly constructed and is typical of the early 18th century gardens when the formality of hedges and flower beds were swept away to be replaced by a more natural setting. This is the influence of Capability Brown and his contemporaries, who wanted to demonstrate through the gardens of the aristocracy how man can tame nature. The gardens blend into the surrounding countryside by great expanses of grass which often sweep down to water or fields of cattle, bordered not by a hedge or a wall, but by an invisible haha to prevent the animals approaching the house. Clumps of trees are carefully placed to focus the eye and to enhance the natural look. Shrubberies and flowers were generally planted at the side or back of the house so as not to interrupt the view.

The elegant driveway to the Manor

I thought I had better try knocking on the imposing front door, although it seemed a rather unorthodox way of accessing the garden. I tapped but there was no response and, rather impertinently, I peered through the prison-like grids cut into the panels; I could see nothing, just blackness. I hammered slightly harder and then waited before walking back round to the side of the house where I had parked. Silence reigned. I then had the idea of phoning her. But no answer.

Chideock Manor front door

After about another five minutes a woman suddenly appeared whom I subsequently discovered was the owner, Deirdre Coates. I introduced myself as the person on the phone and apologised for being late. ‘Oh! One minute.’ She then disappeared again, to emerge a few minutes later with a beautifully illustrated map. She suggested that I start at the left of the house and go round through the Sundial Garden to the woods before going into the Nuttery and the Glade. ‘And don’t miss the Walled Vegetable Gardens’ she said. I gave her the £10.00, and asked her if she could tell me something about about the history of the garden. She explained that ‘The Colonel’ and her, bought the place in 1996 at which time it was completely wild: ‘Just covered in grass and Laurels everywhere, everything you can see is down to us,’ she told me. ‘We started from scratch. It’s a work in progress.’ I asked about the history of the place and who owned it previously. ‘It belonged to a famous Dorset family,’ she explained. ‘The youngest son was given this house, but the place was in disarray when we took it over. We had some photographs to go on but no original designs.’

She was clearly a busy woman so I didn’t persist with more questions and instead walked as directed where I came across the impressive parterre, bordered by a long pleached lime pergola. The parterre is a sophisticated development of the knot garden and was a feature typical of the Italian Renaissance of the 17th and 18th centuries, pre Capability Brown era, when formality was key. They were placed where they would be easily viewed from the upstairs of the house so to be seen in their full glory, as indeed is the one here. Large gardens were traditionally based on a hortus conclusus, literally an enclosed garden, which consisted of spaces, often a series of geometric shapes resembling outdoor rooms, decorated by topiary, pergolas, pavilions and grottos, dotted with classical sculptures and all enclosed by immaculately cut hedges. Garden design in Britain had undergone various phases, in turn influenced by the Italians, the Dutch and the French, when English designers were so dazzled by the gardens of Versailles that they tried to recreate them for the Aristocracy here, albeit on much smaller scales.

The Parterre at Chideock Manor

The (pleached) Lime Walk (Tilia europaea)

I read that the Coates’ had no drawings of the original design of their garden but that they discovered photographs from the early 20th century taken by an Irish woman who was a frequent visitor to the Manor, Ermyngarde de la Poer. After studying horticulture for three years at the RHS, Deirdre Coates then began her restoration project, to restore the gardens to their former glory, with the help of her husband, basing their designs on De La Poer’s photographs.

I then got somewhat side-tracked reading the history of the estate. Since the Norman Conquest it had been owned by just four families, one of whom, the Chideocks, had built Chideock Castle here in 1380. It was passed to the Arundells and then to the Welds who built Chideock Manor in 1810.

Chideock Castle

The history becomes particularly interesting in the 16th and 17th centuries during the Arundell’s occupation. A well known Catholic family, they provided a refuge for priests at the time when it was a treasonable offence for Catholics to carry out their priestly duties. Unfortunately many of them came to sticky ends, including Thomas Pilchard, chaplain to the family at Chideock Castle, whom, along with his two companions, the Arundells kept hidden for two years, probably in priest-holes. Sadly they were discovered and one died in prison whilst the other two were hanged, drawn and quartered.

Hanged, drawn and quartered; the penalty for High Treason

The next man to have the job as Chaplain was John Cornelius. Sadly he was betrayed by a servant and arrested at the Castle, and along with three other local Catholic men, tried for treason. They were executed in Dorchester and became known as the Chideock Martyrs.

Cornelius’ replacement to this perilous role was a young man called Hugh Green who became the family Chaplain in 1612. He was also discovered at the castle. He made a run for it but was arrested on Lyme Cobb where he’d hoped to escape by boat to France. In 1642 he was also executed in Dorchester.

The Martyr Hugh Green

Thereafter the locals started to worship secretly in a barn on the estate, the same spot where the little Church of Our Lady Queen of Martyrs now stands, attached to the Manor. The wall around it appeared to contain ancient relics, one with a date, possibly 1604. But whether this was an old grave or a reference to the Chideock Martyrs is unclear, and there was no one to ask. It is impossible to know if Chideock Castle had gardens here, most castles did have gardens which were mainly designed for entertainment and hunting.

The wall around the church

The Church of the Lady Queen of Martyrs at the end of the bog garden

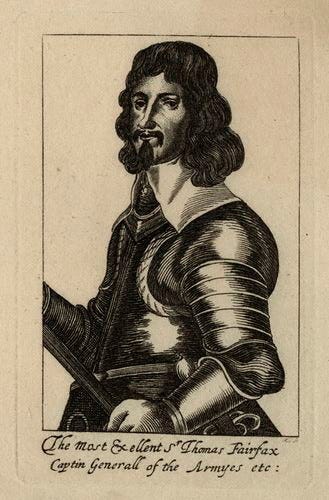

During the Civil War, Catholic Chideock was a staunch Royalist stronghold. The Arundells and the Welds garrisoned their mansions but in 1643 Captain Thomas Pyne captured Chideock Castle for Parliament, taking fifty prisoners. The following year the Cavaliers re-took it and held it for seven months until 1645 when the Parliamentarians stormed the castle again and captured one hundred Royalists. For a time, General Thomas Fairfax, the Parliamentary Commander-in-Chief of the New Model Army, (until he was ousted by Cromwell), had his headquarters in nearby Chideock House. These Roundheads (the derogatory term to describe the New Model Army soldiers due to their short cropped hair, rather than the ringlets of the Cavaliers), ordered the destruction of the castle that same year.

Etching of Thomas Fairfax, Commander in Chief of the Parliamentarians, (despite his ringlets) National Gallery

Thus the only sign left of the castle are a few old stones and a cross marking the spot. But whilst I wandered around this exceptionally beautiful and peaceful garden, I thought about Roundheads and Cavaliers and was reminded of the Civil War re-enactments in Lancaster. In the weeks building up to this annual event you would frequently see ‘soldiers’ from each side, ambling slowly in their heavy, clinking, homemade chainmail towards Lancaster Castle. I could just about conjure up the image of similarly dressed men fighting over little Chideock.

It seems that the Manor Garden lost its glory post 1920, or perhaps not till the WW2 years when many gardens were recommissioned for more useful purposes. How I would love to see Ermyngarde de la Poer’s photographs, to appreciate the inspiration and understand how closely the Coates had restored it to its original glory.

What really stood out for me were the elements of surprise and a great sense of exploration and discovery which the garden created, which may have been enhanced by the fact that I was clearly the only visitor here which allowed my imagination to take off somewhat. I would turn a corner to be gobsmacked by a whole new vista and each with a portal at the end inviting you to venture further and see what lies beyond. The Yew Walk felt militaristic with its turret-shaped Taxus baccata. A magnificent Rhododendron loomed over it, vivid, pink petals falling onto the moat-like path like drops of blood. In contrast, round a corner was a marshy stream bordered by tree ferns, (Dicksonia antarcticas), whose fronds were in their fiddlehead state of unfurling. Here the enormous range of dense foliage gave it a wild, lush and exotic feel. As I walked to The Wilderness area via winding paths and bridges over streams, I thought what a great film-set this would make for a gothic romance, with its lichen covered statues and grottoes reflected in the lily-covered ponds. I half expected to see the Lady of Shalott floating by.

The Yew Walk with the magnificent Rhododendron

Unfurling fiddleheaded fronds of Dicksonia antarctica (Tree Ferns)

To The Wilderness

Classical statue

The Pond

The more I saw of this garden the more I thought that it couldn’t have ever been more wonderful than it is today. For a start, there must be so many more species here now than there were in English gardens in the early nineteenth century; then they had yet to experience the full benefit of the Victorian obsession with plant hunting. Usefully, many of the plants were labelled, including the unusual Podophyllum versipelle ‘Spotty Dotty’ (Chinese May Apple). Its dappled, lime-green leaves popped out amongst the expanse of wild garlic. This specific Podophyllum is a relatively new plant to British gardens and is useful for providing some spotty dotty interest in boggy or shady areas. Low growing, they have large, but poisonous apple-like fruits.

Podophyllum versipelle ‘Spotty Dotty Chinese May Apple

The gorgeous scented cream flowers of Viburnum plicatum shone against the various crimson shades of a hundred year old Acer palmatum. And there was a wonderful choice of idyllic places to rest and enjoy it all; whether a bench in a vegetated grotto or a stone seat with an enchanting view across the lake; I could have spent hours just sitting there taking it all in.

Lichen covered bench

Just as I was admiring a Handkerchief Tree, a rustling bought me back to reality. A sprightly man, rather alarmingly and ferociously swiping the grass with a long stick, but wearing a tweed jacket and wellies rather than armour, lumbered towards me. ‘Davidia involucrata!’ he shouted. It took me a few minutes to comprehend what he was saying. He emerged from the long grass, his thin face and rather watery, but keen eyes, darting from tree to me and back. ‘Also known as the Ghost Tree,’ he said loudly, despite me being just feet from him. Ah, perhaps this is the Colonel I thought to myself, the tendency to shout as if in front of a battalion suggested as much. ‘Hello. It’s fantastic!’ I said. ‘But I know it as the Handkerchief Tree?’ ‘Hmm. A very fine specimen too.’ he said, ignoring my comment. ‘Yes the bracts, they are bracts you know, not leaves, are like apparitions! You should see them at dusk hovering and glowing.’ He waved his stick up at the tree as if he might swipe a few of them away. The thought of roaming alone around this gothic garden at night was not especially appealing. The ghosts of all those priests, I thought.

Davidia involucrata (Ghost Tree or Handkerchief Tree)

Whilst I could not be sure whether he was the Colonel or an employed gardener, he was in any event, most amenable. Annoyingly I forgot to ask him about the stone relics in the wall. But I complemented him on the design and the extensive and interesting planting and together we admired the trees. In the Pinetum was a Wollemi Pine, Wollemia nobilis, a living fossil, related to the Monkey Puzzle. I had come across this in Amsterdam Botanic Garden where I had learnt how the species, the sole one in the genus Wollemia, had only been discovered in 1994, very recently considering it is around 200 million years old. It was found in an Australian rainforest by David Nobel, thus the specific name, nobilis, who was, I read, rather bizarrely looking for new canyons. (I didn’t know there were still undiscovered canyons in Australia). The tree has distinctive bubbly, dark brown bark which, it is said, resembles coco pops. It really does have a primitive appearance, maybe because the side branches rarely branch further. At the end of each a cone will eventually develop before the branch dies. An endangered species, many of them came under threat of destruction from the recent wildfires in Australia, but fortunately firefighters saved most of them.

Wollemia nobilis (Wollemi Pine) in Chideock Manor Pinetum

Clearly no expense has been spared on Chideock Manor Garden, and I wondered how many gardeners they had to keep it so beautiful. ‘Oh we have a good team here!’ the ‘Colonel’ announced when I asked him. And with that it clearly occurred to him that he must get on. ‘You must see the Kitchen garden too,’ he instructed. So I left him to it and made my way through the Birch Grove to the lake where a little rotten boat, which reminded me of the end scene in Du Maurier’s Rebecca, completed the picture of glorious decaying elegance.

The Lake at Chideock

I could have spent hours enjoying the view and feeling inspired by thoughts of gardens and history but I needed to see these infamous kitchen gardens before they closed. Indeed they were extraordinary with military-type topiary, strutting the beds, resembling a giant game of chess being played out; perhaps a tribute to the victims of all those battles on this ground between the Roundheads and the Cavaliers.

The Walled Garden

I reluctantly left the gardens and promised myself to come again to soak up the environment in a different season.

The following day I climbed a footpath up through nearby woods carpeted with the indigo of bluebells, up on to the open heathland of Haredown Hill, punctuated by clumps of bright yellow gorse. From here you can see the counties of Dorset and Devon and a wonderful, sparkling glimpse of the sea.

A carpet of Bluebells (Hyacinthoides non-scripta)

I tried to imagine those events of the 17th century and what it would be like to go back in time; would people be roaming these hills, women searching for herbs perhaps? Maybe Hugh Green would have scrambled up here, panicking, en-route to his attempted escape from Lyme Regis. In one way the place feels steeped in history, although the landscape may be much the same as it is now. Bluebells, gorse and ferns, Lords and Ladies, Addersmeat and Pennywort, no doubt would have been known by other local names then, but all I expect thriving here 400 years ago. Let’s hope they will still be here 400 years from now.

Haredown Hill in Spring

Wow - what an amazing place. You bring it to life with your vivid descriptions of its history and its development over the years.